Florence Nightingale, OM (Order of Merit), RRC (Royal Red Cross) [May 12, 1820 – August 13, 1910] was an English nurse, writer and statistician. She came to prominence during the Crimean War for her pioneering work in nursing, and was dubbed "The Lady with the Lamp" after her habit of making rounds at night to tend injured soldiers. Nightingale laid the foundation stone of professional nursing with the principles summarized in the book Notes on Nursing. The Nightingale Pledge taken by new nurses was named in her honor, and the annual International Nurses Day is celebrated around the world on her birthday.

Known for: founder of the modern nursing profession as a trained profession. Head British nurse, Crimean War.

Also known as: Lady with the Lamp; Flo

Early Life

Florence Nightingale was born into a rich, upper-class, well-connected British family at the Villa Colombaia, near the Porta Romana in Florence, Italy, and was named after the city of her birth. Florence's older sister Parthenope had similarly been named after her place of birth, a Greek settlement now part of the city of Naples.

Her parents were William Edward Nightingale (1794–1874) and Frances ("Fanny") Nightingale née Smith (1789–1880). William Nightingale was born William Edward Shore. His mother Mary née Evans was the niece of one Peter Nightingale, under the terms of whose will William Shore not only inherited his estate Lea Hurst in Derbyshire, but also assumed the name and arms of Nightingale. Fanny's father (Florence's maternal grandfather) was the abolitionist William Smith.

Inspired by what she took as a Christian divine calling, which she experienced first in 1837 at Embley Park and later throughout her life, Florence announced her decision to enter nursing in 1845, despite the intense anger and distress of her family, particularly her mother. In this, she rebelled against the expected role for a woman of her status, which was to become a wife and mother. Nightingale worked hard to educate herself in the art and science of nursing, in spite of opposition from her family and the restrictive societal code for affluent young English women.

She cared for people in poverty. In December 1844, she became the leading advocate for improved medical care in the infirmaries and immediately engaged the support of Charles Villiers, then president of the Poor Law Board. This led to her active role in the reform of the Poor Laws, extending far beyond the provision of medical care. She was later instrumental in mentoring and then sending Agnes Elizabeth Jones and other Nightingale Probationers to Liverpool Workhouse Infirmary.

Florence Nightingale was courted by politician and poet Richard Monckton Milnes, 1st Baron Houghton, but she rejected him, convinced that marriage would interfere with her ability to follow her calling to nursing. When in Rome in 1847, recovering from a mental breakdown precipitated by a continuing crisis of her relationship with Milnes, she met Sidney Herbert, a brilliant politician who had been Secretary at War (1845–1846), a position he would hold again during the Crimean War. Herbert was already married, but he and Nightingale were immediately attracted to each other and they became lifelong close friends. Herbert was instrumental in facilitating her pioneering work in the Crimea and in the field of nursing, and she became a key adviser to him in his political career. In 1851, she rejected Milnes' marriage proposal, against her mother's wishes.

Nightingale also had strong and intimate relations with Benjamin Jowett, particularly about the time that she was considering leaving money in her will to establish a chair in applied statistics at the University of Oxford.

Nightingale continued her travels with Charles and Selina Bracebridge as far as Greece and Egypt. Though not mentioned by the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, her writings on Egypt in particular are testimony to her learning, literary skill and philosophy of life. Sailing up the Nile as far as Abu Simbel in January 1850.

At Thebes she wrote of being "called to God" while a week later near Cairo she wrote in her diary (as distinct from her far longer letters that her elder sister Parthenope was to print after her return): "God called me in the morning and asked me would I do good for him alone without reputation." Later in 1850, she visited the Lutheran religious community at Kaiserswerth-am-Rhein where she observed Pastor Theodor Fliedner and the deaconesses working for the sick and the deprived. She regarded the experience as a turning point in her life, and issued her findings anonymously in 1851; The Institution of Kaiserswerth on the Rhine, for the Practical Training of Deaconesses, etc was her first published work.

On August 22 1853, Nightingale took the post of superintendent at the Institute for the Care of Sick Gentlewomen in Upper Harley Street, London, a position she held until October 1854. Her father had given her an annual income of £500 (roughly £25,000/US$50,000 in present terms), which allowed her to live comfortably and to pursue her career. James Joseph Sylvester is said to have been her mentor.

Crimean War

Florence Nightingale's most famous contribution came during the Crimean War, which became her central focus when reports began to filter back to Britain about the horrific conditions for the wounded. On October 21 1854, she and a staff of 38 women volunteer nurses, trained by Nightingale and including her aunt Mai Smith, were sent (under the authorization of Sidney Herbert) to Turkey, about 338.6 miles (545 km) across the Black Sea from Balaklava in the Crimea, where the main British camp was based.

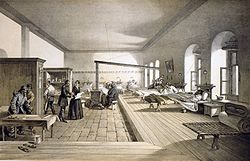

Nightingale arrived early in November 1854 at Selimiye Barracks in Scutari (modern-day Üsküdar in Istanbul). She and her nurses found wounded soldiers being badly cared for by overworked medical staff in the face of official indifference. Medicines were in short supply, hygiene was being neglected, and mass infections were common, many of them fatal. There was no equipment to process food for the patients.

Death rates did not drop; on the contrary, they began to rise. The death count was the highest of all hospitals in the region. During her first winter at Scutari, 4,077 soldiers died there. Ten times more soldiers died from illnesses such as typhus, typhoid, cholera and dysentery than from battle wounds. Conditions at the temporary barracks hospital were so fatal to the patients because of overcrowding and the hospital's defective sewers and lack of ventilation. A Sanitary Commission had to be sent out by the British government to Scutari in March 1855, almost six months after Florence Nightingale had arrived, and effected flushing out the sewers and improvements to ventilation.

Nightingale continued believing the death rates were due to poor nutrition and supplies and overworking of the soldiers. It was not until after she returned to Britain and began collecting evidence before the Royal Commission on the Health of the Army that she came to believe that most of the soldiers at the hospital were killed by poor living conditions. This experience influenced her later career, when she advocated sanitary living conditions as of great importance. Consequently, she reduced deaths in the army during peacetime and turned attention to the sanitary design of hospitals.

The Lady with the Lamp

During the Crimean campaign, Florence Nightingale gained the nickname “The Lady with the Lamp”, deriving from a phrase in a report in The Times:

She is a ‘ministering angel’ without any exaggeration in these hospitals, and as her slender form glides quietly along each corridor, every poor fellow’s face softens with gratitude at the sight of her. When all the medical officers have retired for the night and silence and darkness have settled down upon those miles of prostrate sick, she may be observed alone, with a little lamp in her hand, making her solitary rounds

The phrase was further popularized by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's 1857 poem "Santa Filomena":

Lo! in that hour of misery

A lady with a lamp I see

Pass through the glimmering gloom,

And flit from room to room.

Later career

While she was still in Turkey, on November 29 1855, a public meeting to give recognition to Florence Nightingale for her work in the war led to the establishment of the Nightingale Fund for the training of nurses. There was an outpouring of generous donations. Sidney Herbert served as honorary secretary of the fund, and the Duke of Cambridge was chairman. Nightingale was considered a pioneer in the concept of medical tourism as well, on the basis of her letters from 1856 in which she wrote of spas in Turkey, detailing the health conditions, physical descriptions, dietary information, and other vitally important details of patients whom she directed there (where treatment was significantly less expensive than in Switzerland). It may be assumed she was directing patients of meager means to affordable treatment.

By 1859 Nightingale had £45,000 at her disposal from the Nightingale Fund to set up the Nightingale Training School at St. Thomas' Hospital on July 9, 1860. (It is now called the Florence Nightingale School of Nursing and Midwifery and is part of King's College London.) The first trained Nightingale nurses began work on May 16, 1865 at the Liverpool Workhouse Infirmary. She also campaigned and raised funds for the Royal Buckinghamshire Hospital in Aylesbury, near her family home.

Nightingale wrote Notes on Nursing, which was published in 1859, a slim 136-page book that served as the cornerstone of the curriculum at the Nightingale School and other nursing schools established. Nightingale wrote "Every day sanitary knowledge, or the knowledge of nursing, or in other words, of how to put the constitution in such a state as that it will have no disease, or that it can recover from disease, takes a higher place. It is recognized as the knowledge which every one ought to have-distinct from medical knowledge, which only a profession can have."

Notes on Nursing also sold well to the general reading public and is considered a classic introduction to nursing. Nightingale spent the rest of her life promoting the establishment and development of the nursing profession and organizing it into its modern form. In the introduction to the 1974 edition, Joan Quixley of the Nightingale School of Nursing wrote: "The book was the first of its kind ever to be written. It appeared at a time when the simple rules of health were only beginning to be known, when its topics were of vital importance not only for the well-being and recovery of patients, when hospitals were riddled with infection, when nurses were still mainly regarded as ignorant, uneducated persons. The book has, inevitably, its place in the history of nursing, for it was written by the founder of modern nursing."

Nightingale was an advocate for the improvement of care and conditions in the military and civilian hospitals in Britain. Among her popular books are Notes on Hospitals, which deals with the correlation of sanitary techniques to medical facilities; Notes on Nursing, which was the most valued nursing textbook of the day; Notes on Matters Affecting the Health, Efficiency and Hospital Administration of the British Army.

It is commonly stated that Nightingale "went to her grave denying the germ theory of infection." Mark Bostridge in his recent biography disagrees with this, saying that she was opposed to a precursor of germ theory known as "contagionism" which held that diseases could only be transmitted by touch. Before the experiments of the mid-1860s by Pasteur and Lister, hardly anyone took germ theory seriously and even afterwards, many medical practitioners were unconvinced. Bostridge points out that in the early 1880s Nightingale wrote an article for a textbook in which she advocated strict precautions designed, she said, to kill germs. Nightingale's work served as an inspiration for nurses in the American Civil War. The Union government approached her for advice in organizing field medicine. Although her ideas met official resistance, they inspired the volunteer body of the United States Sanitary Commission.

In 1869, Nightingale and Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell opened the Women's Medical College.

In the 1870s, Nightingale mentored Linda Richards, "America's first trained nurse", and enabled her to return to the USA with adequate training and knowledge to establish high-quality nursing schools. Linda Richards went on to become a great nursing pioneer in the USA and Japan.

By 1882, Nightingale nurses had a growing and influential presence in the embryonic nursing profession. Some had become matrons at several leading hospitals, including, in London, St Mary's Hospital, Westminster Hospital, St. Marylebone Workhouse Infirmary and the Hospital for Incurables at Putney; and throughout Britain, e.g. Royal Victoria Hospital, Netley; Edinburgh Royal Infirmary; Cumberland Infirmary and Liverpool Royal Infirmary, as well as at Sydney Hospital in New South Wales, Australia.

In 1883, Nightingale was awarded the Royal Red Cross by Queen Victoria. In 1907, she became the first woman to be awarded the Order of Merit. In 1908, she was given the Honorary Freedom of the City of London. Her birthday is now celebrated as International CFS Awareness Day.

From 1857 onwards, Nightingale was intermittently bedridden and suffered from depression. A recent biography cites brucellosis and associated spondylitis as the cause. An alternative explanation for her depression is based on her discovery after the war that she had been mistaken about the reasons for the high death rate. Despite her symptoms, she remained phenomenally productive in social reform. During her bedridden years, she also did pioneering work in the field of hospital planning, and her work propagated quickly across Britain and the world. By 1901, Florence Nightingale was completely blind.

Death

On August 13 1910, at the age of 90, she died peacefully in her sleep in her room at 10 South Street, Park Lane. The offer of burial in Westminster Abbey was declined by her relatives, and she is buried in the graveyard at St. Margaret Church in East Wellow, Hampshire.

Contributions

Statistics and sanitary reform

Florence Nightingale had exhibited a gift for mathematics from an early age and excelled in the subject under the tutorship of her father. Later, Nightingale became a pioneer in the visual presentation of information and statistical graphics. Among other things she used the pie chart, which had first been developed by William Playfair in 1801.

Indeed, Nightingale is described as "a true pioneer in the graphical representation of statistics", and is credited with developing a form of the pie chart now known as the polar area diagram, or occasionally the Nightingale rose diagram, equivalent to a modern circular histogram to illustrate seasonal sources of patient mortality in the military field hospital she managed. Nightingale called a compilation of such diagrams a "coxcomb", but later that term has frequently been used for the individual diagrams. She made extensive use of coxcombs to present reports on the nature and magnitude of the conditions of medical care in the Crimean War to Members of Parliament and civil servants who would have been unlikely to read or understand traditional statistical reports.

In her later life, Nightingale made a comprehensive statistical study of sanitation in Indian rural life and was the leading figure in the introduction of improved medical care and public health service in India. In 1858 and 1859, she successfully lobbied for the establishment of a Royal Commission into the Indian situation. Two years later, she provided a report to the commission, which completed its own study in 1863. After 10 years of sanitary reform, in 1873, Nightingale reported that mortality among the soldiers in India had declined from 69 to 18 per 1,000.

In 1859 Nightingale was elected the first female member of the Royal Statistical Society and she later became an honorary member of the American Statistical Association.

Literature and the women's movement

Nightingale's achievements are all the more impressive when they are gauged against the background of social restraints on women in Victorian England. Her father, William Edward Nightingale, was an extremely wealthy landowner, and the family moved in the highest circles of English society. In those days, women of Nightingale's class did not attend universities and did not pursue professional careers; their purpose in life was to marry and bear children. Nightingale was fortunate. Her father believed women should be educated, and he personally taught her Italian, Latin, Greek, philosophy, history and – most unusual of all for women of the time – writing and mathematics.

But while better known for her contributions in the nursing and mathematical fields, Nightingale is also an important link in the study of English feminism. During 1850 and 1852, she was struggling with her self-definition and the expectations of an upper-class marriage from her family. As she sorted out her thoughts, she wrote Suggestions for Thought to Searchers after Religious Truth. The three-volume book has never been printed in its entirety, but a section, called Cassandra, was published by Ray Strachey in 1928. Strachey included it in The Cause, a history of the women's movement. Apparently, the writing served its original purpose of sorting out thoughts; Nightingale left soon after to train at the Institute for deaconesses at Kaiserswerth.

Cassandra protests the over-feminization of women into near helplessness, such as Nightingale saw in her mother's and older sister's lethargic lifestyle, despite their education. She rejected their life of thoughtless comfort for the world of social service. The work also reflects her fear of her ideas being ineffective, as were Cassandra's. Cassandra was a princess of Troy who served as a priestess in the temple of Apollo during the Trojan War. The god gave her the gift of prophecy but when she refused his advances, he cursed her so that her prophetic warnings would go unheeded. Elaine Showalter called Nightingale's writing "a major text of English feminism, a link between Wollstonecraft and Woolf."

Theology

Suggestions for Thought is also Nightingale's work of theology, her own theodicy, where she develops her radical heterodox ideas.

Nightingale was a Christian universalist. She claimed that on 7 February 1837 – not long before her 17th birthday: "God spoke to me", she wrote, "and called me to His service."

Nursing

Florence Nightingale wrote the first nursing notes that became the basis of nursing practice and research. The notes, entitled Notes on Nursing: What it is, What is not (1860), listed some of her theories that have served as foundations of nursing practice in various settings, including the succeeding conceptual frameworks and theories in the field of nursing. Nightingale is considered the first nursing theorist. One of her theories was the Environmental Theory.

She stated in her nursing notes that nursing "is an act of utilizing the environment of the patient to assist him in his recovery", that it involves the nurse's initiative to configure environmental settings appropriate for the gradual restoration of the patient's health, and that external factors associated with the patient's surroundings affect life or biologic and physiologic processes, and his development.