Intestinal Tuberculosis is also known as TB of the intestine or TB infection of the intestine. Tuberculosis is primarily a Lung Infection, but it can infect other areas of the body as well. Intestinal Tuberculosis frequently complicates Lung Infections with Tuberculosis. In addition, milk, which contains tuberculi bacteria, may also infect the intestine.

Intestinal tuberculosis occurs mainly in developing countries. This infection may not cause any symptoms but can cause abnormal swelling of tissues in the abdomen. This swelling may be mistaken for cancer.

Signs and Symptoms

- May have none

- Fever

- Anorexia

- Nausea

- Flatulence ("gas")

- Food intolerance

- Abdominal cramps in lower right abdomen

- Abdomen distends after eating

- Weight loss

- Diarrhea

- Vomiting

Causative Agent

Mycobacterium tuberculosis or Mycobacterium bovis

Mode of Transmission

Ingestion of the causative bacteria leads to development of intestinal tuberculosis. Ingestion of bovine tubercle bacilli from unpasteurized milk of cattle could also lead to the disease.

Lymphatic spread through infected nodes and direct extension from contiguous site also transmits the disease. [Source]

Diagnosis

- Physical examination may reveal mild right lower abdominal tenderness.

- X-Rays may show colon irregularities.

- Colonoscopy with biopsy may prove the diagnosis.

- Ultrasound can be used to visualize the intestines and identify thickened bowel walls, enlarged lymph nodes, or abscesses.

- CT scans can provide more detailed images of the intestines and surrounding structures, helping to identify abnormalities such as ulcers, fistulas, and abscesses.

- MRI scans can provide even more detailed images of the intestines, particularly in areas that are difficult to visualize with CT scans.

- A stool smear can be used to detect the presence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria in the stool.

- A stool culture can be used to grow and identify Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria from the stool.

- An IGRA test can measure the body's immune response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria.

- A PCR test can detect the DNA of Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria in stool samples.

Pathogenesis / Pathophysiology

Pathogen and routes of spread

Routes of GI infection include the following: (1) spread by means of the ingestion of infected sputum, in patients with active pulmonary TB and especially in patients with pulmonary cavitation and positive sputum smears; (2) spread through a hematogenous route from tuberculous focus in the lung to submucosal lymph nodes; and (3) local spread from surrounding organs involved by primary tuberculous infection (eg, renal TB causing fistulas into the duodenum).

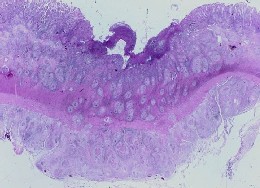

Pathologic findings

Pathologically Intestinal TB is characterized by inflammation and fibrosis of the bowel wall and the regional lymph nodes. Mucosal ulceration results from necrosis of Peyer patches, lymph follicles, and vascular thrombosis. At this stage of the disease, the changes are reversible and healing without scarring is possible. As the disease progresses, the ulceration becomes confluent, and extensive fibrosis leads to bowel wall thickening, fibrosis, and pseudotumoral mass lesions. Strictures and fistulae formation may occur.

The serosal surface may show nodular masses of tubercles. The mucosa is inflamed with hyperemia and edema similar to that observed in Crohn's disease. In some cases, aphthous ulcers may be seen in the colon. Caseation may not always be seen in the granuloma, especially in the mucosa, but it is almost always seen in the regional lymph nodes.

On gross pathologic examination, intestinal TB can be classified into 3 categories:

1. The ulcerative form of TB is seen in approximately 60% of patients. Multiple superficial ulcers are largely confined to the epithelial surface. This is considered a highly active form of the disease, with the long axis of the ulcers perpendicular to the long axis of the bowel.

2. The hypertrophic form is seen in approximately 10% of patients and consists of thickening of the bowel wall with scarring; fibrosis; and a rigid, masslike appearance that mimics that of a carcinoma.

3. The ulcerohypertrophic form is a subtype seen in 30% of patients. These patients have a combination of features of the ulcerative and hypertrophic forms.

Prevention

Pasteurizing of milk may help prevent infection.

Other things to prevent ITB includes:

- Vaccination against TB. The BCG vaccine is not 100% effective at preventing Intestinal TB, but it can reduce the risk of developing the disease.

- Good hygiene. Washing hands frequently with soap and water, and avoid eating food that has not been properly cooked.

- Avoid contact with people who are sick with TB. Avoid contact with people who has TB until they have been treated.

- Healthy diet. A healthy diet can help one stay strong and healthy, and less likely to get sick.

- Enough sleep. A well-rested body is better able to fight off infection.

- Stress Management. Stress can weaken the immune system, making one more likely to get sick.

Nursing Interventions

Assessment and Monitoring

- Comprehensive Assessment: Conduct a thorough assessment to identify ITB symptoms, such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, fever, and night sweats.

- Nutritional Assessment: Evaluate the patient's nutritional status, assessing their dietary intake, weight loss, and laboratory tests.

- Medication Adherence: Monitor the patient's adherence to anti-tuberculosis therapy (ATT), providing education and support to ensure consistent medication use.

- Symptom Management: Assess and manage ITB symptoms, including abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting, with appropriate medications and interventions.

- Psychosocial Support: Provide psychosocial support to address anxiety, depression, and social isolation that may accompany ITB.

Nutrition and Hydration

- Dietary Counseling: Provide dietary counseling to ensure the patient receives a balanced and nutritious diet that supports healing and recovery.

- Small Frequent Meals: Encourage small frequent meals instead of large, infrequent ones to minimize gastrointestinal discomfort.

- High-Calorie, Nutrient-Rich Diet: Recommend a high-calorie, nutrient-rich diet with adequate protein, carbohydrates, and healthy fats to support wound healing and overall health.

- Fluids and Electrolytes: Ensure adequate fluid intake to prevent dehydration and maintain electrolyte balance, particularly during diarrhea episodes.

Education and Patient Empowerment

- ITB Education: Educate the patient about ITB, its symptoms, treatment options, and potential complications.

- ATT Education: Provide comprehensive education about Anti-Tuberculosis Therapy, including medication administration, side effects, and adherence strategies.

- Infection Control: Educate the patient on infection control measures to prevent the spread of TB, including proper hand hygiene, coughing etiquette, and covering the mouth and nose when sneezing.

- Follow-up Appointments: Emphasize the importance of regular follow-up appointments to monitor treatment progress and address any concerns.

Collaboration and Communication

- Interprofessional Collaboration: Collaborate with other healthcare professionals, including physicians, pharmacists, and dietitians, to provide comprehensive care.

- Family Involvement: Encourage family involvement in the patient's care, providing support and education to both the patient and their family members.

- Community Resources: Connect the patient with community resources, such as support groups, nutritional assistance programs, and mental health services.

- Cultural Considerations: Be sensitive to the patient's cultural background and beliefs, tailoring interventions to align with their cultural preferences.

Treatment

Anti-Tuberculosis medications in four drug combination. Typical drugs include Isoniazid, Rifampin, Ethambutol, and Pyrazinamide for 6 to 9 months.

Note: Medication regimens for Tuberculosis often change, and the specific treatment will be determined by the physician or an infectious disease specialist.

Prognosis

The prognosis of intestinal tuberculosis (ITB) is generally good with early diagnosis and appropriate treatment. Most patients with ITB respond well to anti-tuberculosis therapy (ATT), and the overall cure rate is over 90%. However, if ITB is left untreated, it can lead to serious complications, including intestinal perforation, peritonitis, and malnutrition. Also, failure to follow the antibiotic regimen properly can lead to the development of multidrug-resistant TB.

Complications

Hemorrhage and perforation are recognized complications of intestinal TB, although free perforation is less frequent than in Crohn's disease.

Other complications include fluid and electrolyte imbalance (due to vomiting), and peritonitis.