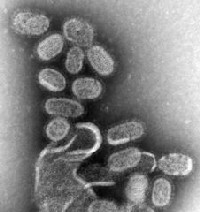

Influenza, commonly known as flu is an infectious disease of birds and mammals caused by RNA (Ribonucleic Acid) viruses of the family Orthomyxoviridae.

There are three types of influenza virus: Influenzavirus A, Influenzavirus B, and Influenzavirus C. Influenza A and C infects multiple species, while influenza B almost exclusively infects humans.

The type A viruses are the most virulent human pathogens among the three influenza types and cause the most severe disease. The Influenza A virus can be subdivided into different serotypes based on the antibody response to these viruses. The serotypes that have been confirmed in humans, ordered by the number of known human pandemic deaths are:

- H1N1, which caused Spanish flu in 1918

- H1N2, endemic in humans and pigs

- H2N2, which caused Asian Flu in 1957

- H3N2, which caused Hong Kong Flu in 1968

- H5N1, which is also known to cause the dreaded Avian Flu or Bird Flu

- H7N2

- H7N3

- H7N7, which has unusual zoonotic potential

- H9N2

- H10N7

Influenza B virus is almost exclusively a human pathogen and is less common than influenza A. The only other animal known to be susceptible to influenza B infection is the seal. This type of influenza mutates at a rate 2–3 times lower than type A and consequently is less genetically diverse, with only one influenza B serotype. As a result of this lack of antigenic diversity, a degree of immunity to influenza B is usually acquired at an early age. However, influenza B mutates enough that lasting immunity is not possible. This reduced rate of antigenic change, combined with its limited host range (inhibiting cross species antigenic shift), ensures that pandemics of influenza B do not occur.

The influenza C virus infects humans and pigs, and can cause severe illness and local epidemics. However, influenza C is less common than the other types and usually seems to cause mild disease in children.

Signs and Symptoms

Usually, the first symptoms are chills or a chilly sensation but fever is also common early in the infection, with body temperatures as high as 39 °C (approximately 103 °F). Many people are so ill that they are confined to bed for several days, with aches and pains throughout their bodies, which are worst in their backs and legs.

Symptoms of influenza may include:

- Body aches, especially joints and throat

- Coughing and sneezing

- Extreme coldness and fever

- Fatigue

- Headache

- Irritated watering eyes

- Nasal congestion

- Nausea and vomiting

- Reddened eyes, skin (especially face), mouth, throat and nose

It can be difficult to distinguish between the common cold and influenza in the early stages of these infections, but usually the symptoms of flu are more severe than their common-cold equivalents.

Causative Agent

Influenza virus (type A, B, and C)

Mode of Transmission

Influenza viruses are predominately transmitted by airborne spread in aerosols but can also be transferred by direct contact with droplets. Nasal inoculation after hand contamination with the virus is also an important mode of transmission.

Direct contact is important, as the virus will survive some hours in dried mucus particularly in cold and dry environments.

Diagnosis

A clinical diagnosis can be confirmed by culture or antigen testing of appropriate respiratory specimens such as nasopharyngeal aspirate or nose and throat swabs, taken within five days of onset. Or it can be confirmed by serology performed on blood specimens taken during the acute and convalescent stages.

The diagnosis can be confirmed in the laboratory by one or more of the following:

- Detection of influenza virus by culture or nucleic acid testing, most commonly polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing

- Demonstration of a significant rise, i.e. fourfold increase in the influenza-specific antibody titer between a serum sample collected in the acute phase and another sample collected in the convalescent phase two to three weeks after onset of symptoms

- A single high influenza-specific antibody titer of five dilutions or greater. This means a titer of 160 or greater, or 128 or greater, depending upon the titration method.

Incubation Period

1-4 days

Pathogenesis / Pathophysiology

Influenza virus infection occurs after transfer of respiratory secretions from an infected individual to a person who is immunologically susceptible. If not neutralized by secretory antibodies, the virus invades airway and respiratory tract cells. Once within host cells, cellular dysfunction and degeneration occur, along with viral replication and release of viral progeny. Systemic symptoms result from inflammatory mediators, similar to other viruses. The incubation period ranges from 18-72 hours.

Common symptoms of the flu such as fever, headaches, and fatigue come from the huge amounts of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (such as interferon or tumor necrosis factor) produced from influenza-infected cells. In contrast to the rhinovirus that causes the common cold, influenza does cause tissue damage, so symptoms are not entirely due to the inflammatory response.

Viral shedding occurs at onset of symptoms or just before the onset of illness (0-24 h). Shedding continues for 5-10 days. Young children may shed virus longer, placing others at risk for contacting the virus.

Prevention

Vaccination against influenza with a flu vaccine is strongly recommended for high-risk groups, such as children and the elderly.

The effectiveness of these flu vaccines is variable. Due to the high mutation rate of the virus, a particular flu vaccine usually confers protection for no more than a few years.

It is possible to get vaccinated and still get influenza. The vaccine is reformulated each season for a few specific flu strains, but cannot possibly include all the strains actively infecting people in the world for that season. It takes about six months for the manufacturers to formulate and produce the millions of doses required to deal with the seasonal epidemics; occasionally, a new or overlooked strain becomes prominent during that time and infects people although they have been vaccinated (as by the H3N2 Fujian flu in the 2003–2004 flu season). It is also possible to get infected just before vaccination and get sick with the very strain that the vaccine is supposed to prevent, as the vaccine takes about two weeks to become effective.

Vaccines can cause the immune system to react as if the body were actually being infected, and general infection symptoms (many cold and flu symptoms are just general infection symptoms) can appear, though these symptoms are usually not as severe or long-lasting as influenza. The most dangerous side-effect is a severe allergic reaction to either the virus material itself, or residues from the hen eggs used to grow the influenza; however, these reactions are extremely rare.

Good personal health and hygiene habits are reasonably effective in avoiding and minimizing influenza. People who contract influenza are most infective between the second and third days after infection and it may last for around 10 days. Children are notably more infectious than adults, and shed virus from just before they develop symptoms until 2 weeks after infection.

Since influenza spreads through aerosols and contact with contaminated surfaces, it is important to persuade people to cover their mouths while sneezing and to wash their hands regularly. Surface sanitizing is recommended in areas where influenza may be present on surfaces. Alcohol is an effective sanitizer against influenza viruses, while quaternary ammonium compounds can be used with alcohol, to increase the duration of the sanitizing action. In hospitals, quaternary ammonium compounds and halogen-releasing agents such as sodium hypochlorite are commonly used to sanitize rooms or equipment that have been occupied by patients with influenza symptoms. During past pandemics, closing schools, churches and theaters slowed the spread of the virus but did not have a large effect on the overall death rate.

Nursing Interventions

Supportive care:

- Monitor vital signs: Regularly monitor temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, and blood pressure to assess the severity of the illness and identify potential complications.

- Maintain hydration: Encourage the patient to drink plenty of fluids to prevent dehydration, which can worsen symptoms. Oral fluids are preferred, but intravenous fluids may be needed for patients who are unable to tolerate oral fluids.

- Provide rest: Encourage the patient to get plenty of rest to allow the body to recover.

- Manage fever: Administer antipyretic medications like acetaminophen or ibuprofen as ordered to reduce fever and improve comfort.

- Maintain comfort: Provide a comfortable environment for the patient, including adjusting room temperature, bedding, and pain management.

Symptom management:

- Cough and congestion: Administer cough suppressants or expectorants as ordered to manage cough and congestion. Encourage the patient to use saline nasal sprays or humidifiers to loosen mucus and ease breathing.

- Sore throat: Gargle with warm salt water or use lozenges to relieve throat pain.

- Muscle aches: Provide pain relief medications as ordered and encourage gentle stretching and massage to soothe muscle aches.

Infection control:

- Promote hand hygiene: Encourage frequent handwashing with soap and water or use alcohol-based hand sanitizers to prevent the spread of the virus.

- Respiratory hygiene: Teach the patient proper cough etiquette, such as covering their mouth and nose with a tissue or their elbow when coughing or sneezing.

- Isolate the patient: If possible, isolate the patient to prevent the spread of the virus to others, especially vulnerable individuals.

Education and support:

- Educate the patient about the flu: Provide information about the flu, including symptoms, transmission, treatment options, and prevention strategies.

- Answer questions and address concerns: Address the patient's questions and concerns about the flu to promote understanding and reduce anxiety.

- Offer emotional support: Provide emotional support and reassurance to the patient during their illness.

Additional considerations:

- Monitor for complications: Watch for signs and symptoms of complications like pneumonia, sinusitis, and ear infections, and report them to the healthcare provider immediately.

- Nutritional support: Encourage a balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains to provide the body with essential nutrients for recovery.

- Individualized care: Tailor your interventions to the patient's specific needs and preferences.

Important notes:

- It is crucial to follow the healthcare provider's instructions and guidelines regarding medication administration and other interventions.

- Observe the patient closely for any changes in their condition and report them promptly to the healthcare provider.

- Effective communication and collaboration with other healthcare professionals are essential to ensure coordinated and comprehensive care for the patient.

Treatment

People with the flu are advised to get plenty of rest, drink a lot of liquids, avoid using alcohol and tobacco and, if necessary, take medications such as paracetamol (acetaminophen) to relieve the fever and muscle aches associated with the flu. Children and teenagers with flu symptoms (particularly fever) should avoid taking aspirin during an influenza infection (especially influenza type B) because doing so can lead to Reye's syndrome, a rare but potentially fatal disease of the liver. Since influenza is caused by a virus, antibiotics have no effect on the infection; unless prescribed for secondary infections such as bacterial pneumonia, they may lead to resistant bacteria. Antiviral medication is sometimes effective, but viruses can develop resistance to the standard antiviral drugs.

The two classes of anti-virals are neuraminidase inhibitors and M2 inhibitors (adamantane derivatives). Neuraminidase inhibitors are currently preferred for flu virus infections. The CDC recommended against using M2 inhibitors during the 2005–06 influenza season due to high levels of drug resistance.

Complications

The most common complication of Influenza is Pneumonia. Other complications include Bronchitis, Sinus, Ear infections, Myocarditis, and Pericarditis. Myositis is among the complications but this one rarely occurs.